Aussies reach out for mental health help in record numbers

Australians struggling with their mental health are reaching out to Lifeline in record numbers.

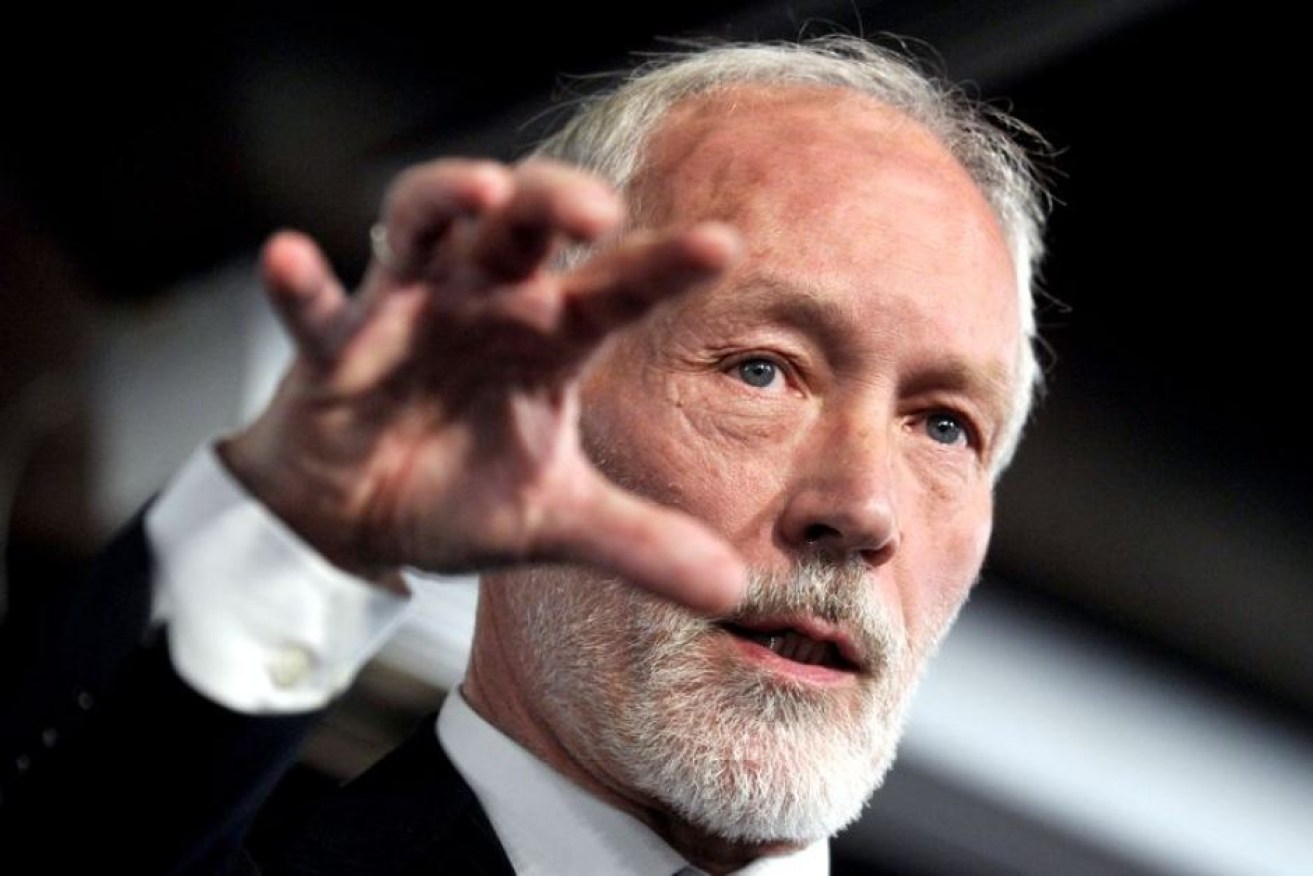

Orygen executive director and former Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry (ABC photo)

Lifeline chairman John Brogden says its 13 11 14 crisis line has received more calls than ever in its 57-year history – with 3326 calls made by Australians in crisis as recently as Tuesday.

Brogden sais on World Suicide Prevention Day and RUOK? Day, Lifeline’s crisis helpline acts like a barometer to the mental wellbeing of the nation.

“We must remind the community that people are really struggling with bushfire recovery and the challenge of COVID-19,” he said in a statement on Thursday.

“There has never been a more important time to reach out to those who you think may be struggling and let them know you care. Your actions can save a life.”

Leading psychiatrist and former Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry says there’s been an upswing in mental health cases, and their severity, since the virus hit Australia in March.

“What we’re seeing, from what my colleagues tell me on the frontline, is about a 20 per cent increase in people presenting,” Prof McGorry told AAP.

“Often in quite acute and complex presentations now too, so there’s definitely an increase in severity.

“All the surveys of the population show a very substantial rise in distress, which we know translates into a surge for the need for care as well.”

Prof McGorry warned the nation’s first economic recession in three decades will be “the most powerful driver of suicide” in future months.

“The suicide increase is projected over the coming months and years, rather than immediately,” he told AAP.

“We have already seen a rise in self-harm and suicidal behaviour.

“It just … hasn’t actually translated into death rates yet.”

On World Suicide Prevention Day and RU OK? Day, Prof McGorry said it wasn’t too late to reduce the potentially-deadly impacts of coronavirus pressures.

He appealed to Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Daniel Andrews, premier of the hardest-hit coronavirus state Victoria, to grasp the enormity of the mental health system’s shortfalls.

Recently-announced $60 million and $32 million mental health packages from state and federal governments are akin to “firing a hose into a raging bushfire”, Prof McGorry, who’s also executive director of youth mental health group Orygen, said.

“They and the whole public are starting to understand this has been a very big sleeping giant and it’s been woken up by the pandemic.

“We’ve got to build the right infrastructure for the 21st century.”

That includes making Beyond Blue and other mental health support centres more digital-friendly to help stem the tide of the current surge, he said.

While some sufferers patiently wait or hesitate to seek help, the charity R U OK? is trying to arm family, friends and colleagues with the skills to have productive mental health conversations.

R U OK? ambassador Megan Barrow, who once suffered from agoraphobia, a fear of being in open or public places, said COVID-19 has forced more people to confront their mental health.

“Crises are an opportunity for learning,” she said.

“I hope that in five years’ time we don’t all forget it.”

Morrison on Thursday told Australians there was hope beyond the coronavirus pandemic.

“There’s a lot of stress, and there’s a lot of pressure on Australians at the moment,” he wrote in an opinion piece published in The West Australian.

“There’s a truth in the saying, a burden shared is a burden halved.

“More than ever, we need conversations about how we’re doing. I want you to know that there is hope, and we will get to the other side of COVID-19.”

More than 10,000 volunteers work with Lifeline to ensure Australians are kept safe.

“This year, we have asked a lot from our volunteers, we are very grateful to all who have worked additional shifts and continually put up their hand to ensure we can be here to support every Australian who needs us,” Brogden said.

While most people know Lifeline as the 13 11 14 suicide prevention crisis line, the organisation is made up of a network of 40 centres operating in 60 communities across the nation which also offers on the ground services to help communities become suicide safe through training, counselling and suicide prevention support groups.

Globally, last year, there were 800,000 lives lost to suicide – one every 40 seconds.

In Australia’s last reporting period (2018), there were 3046 lives lost to suicide.

“With every life lost, there are 135 people – families, friends, colleagues, fellow students, who are left devastated. There are many more who struggle with their own mental wellbeing,” Mr Brogden said.

Lifeline expects its 4500 crisis supporters will talk or chat to more than one million people through its phone and webchat services this year.

The phone service alone receives up to 90,000 calls a month – that’s a person reaching out every 30 seconds.

Lifeline 13 11 14

beyondblue 1300 22 4636

-AAP