Lessons in learning: So many questions that a mere chatbot simply can’t answer

Just a couple of months since its release, artificial intelligence platform ChatGPT has caused concern in many places and panic in others. But while educators, in particular, evaluate its impact, there’s no definitive view of whether it’s a hindrance or a help, writes Brisbane Girls Grammar Principal Jacinda Euler.

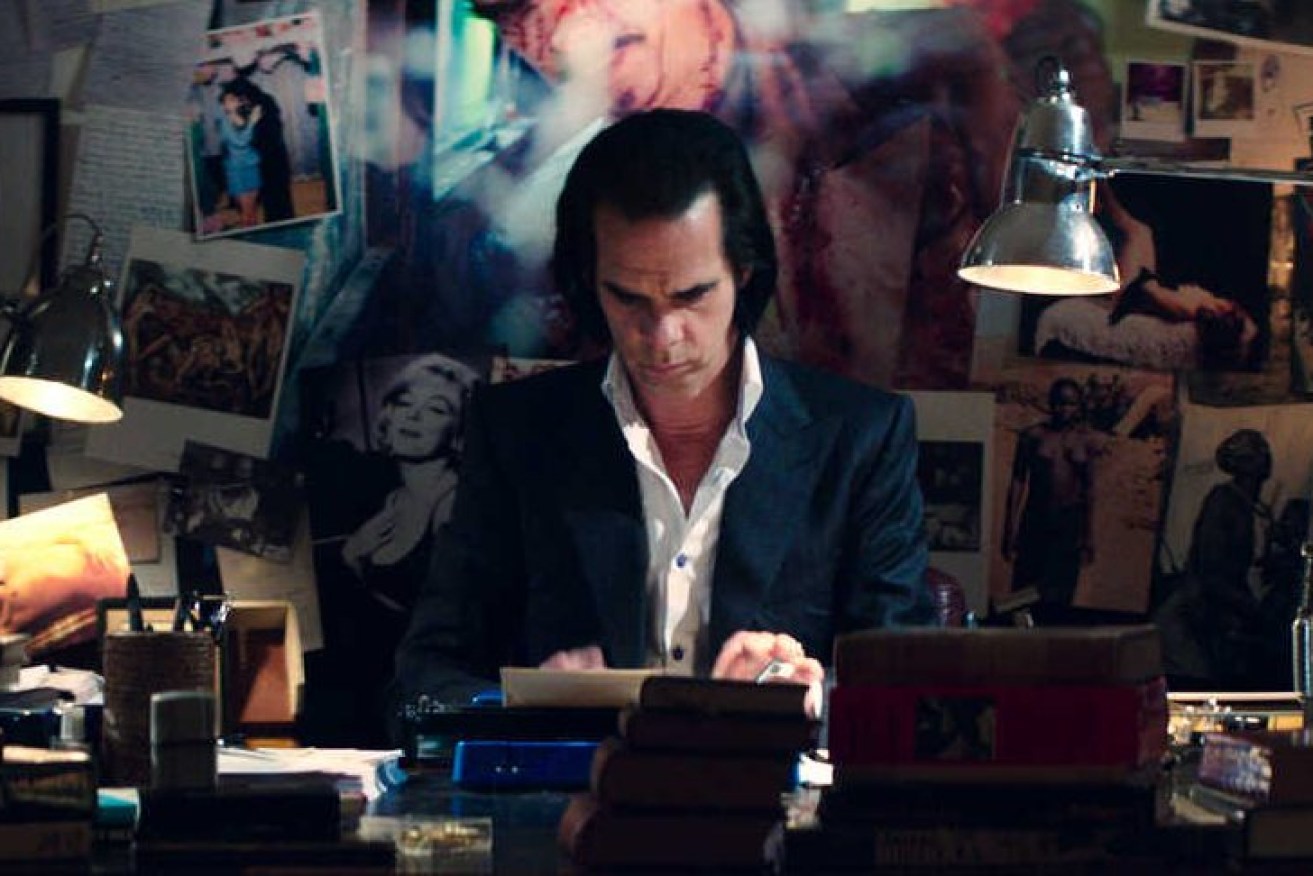

Singer Nick Cave has been vocal in his dismissal of the chatbot, which, he says, lacks "humanness". (Image: Drafthouse Films)

If we thought 2023 was a year we could ease into after three years of chaos, ChatGPT has arrived to quash that notion. The chatbot, making headlines around the world, has stunned many with its ability to answer anything.

Engineered by a Microsoft-backed research lab, ChatGPT can write essays, poems, scripts, lesson plans, and computer code, give feedback on assignments and answer multiple-choice quizzes – in seconds. And while far from perfect, ChatGPT’s responses are humanised in a way not yet seen in Artificial Intelligence, and can be refined and tweaked to produce an endless list of written materials.

Since its launch in November 2022, ChatGPT has, expectedly, drawn criticism, and evoked fear across many sectors, including education. Concerns range from practicalities such as the accuracy and validity of data and possible spread of disinformation, to philosophical ponderings such as ‘how do you attribute plagiarism to a robot?’ and ‘how do we ensure that students are learning the required course and syllabus material and understanding it?’ Will integrity prevail when an answer can be provided in seconds?

BGGS Head of Literature, Meghan Parry, believes these seconds won’t equate to better results.

In the English classroom, novel summaries and generic analytical arguments might be replicated in seconds, but ChatGPT’s answers read like those of someone who hasn’t actually cracked the spine of the novel—our expert teachers are already aware of this “trick” so while using Chat GPT might take fewer Google searches and less editing time, the end result will never be better.

And how could AI possibly hope to capture the essence of being human in its swift responses? Australian songwriter and performer, Nick Cave, declared ChatGPT’s attempt at creating a song ‘in the style of Nick Cave’ as ‘a mockery of what it is to be human’. Cave also described writing a good song as ‘an authentic creative struggle’ that requires what AI will never have: humanness.”

When any new potentially threatening technology is released, there are often immediate calls to restrict it – ‘block or ban’ – contain the problem and it will disappear. While a natural first response, we humans do after all fear the unknown and find comfort in the way ‘things are done’, we know this response is untenable.

Some schools in Queensland and NSW have moved swiftly to ban access to ChatGPT until the technology can be ‘fully assessed’. The effectiveness of this approach will certainly be challenged, given humans, particularly young ones, are quick to find ways to access anything ‘banned’.

And the irony of human ingenuity being used to access artificial intelligence is not lost on any of us. Is the solution one that has been offered by many experts, including educators – to find ways to use this technology responsibly and harness its abilities to assist teachers and students alike?

While the current media interest surrounding this new development stokes our desire for immediate answers, the truth is that we need time to understand ChatGPT and this new evolution of AI technology, before we can discuss how to manage and potentially, in time, harness it.

NY Times Technology Columnist, Kevin Roose, interviewed educators about ChatGPT, and some were, understandably, anxious that this technology would in time render them unnecessary—speculating that if ChatGPT can review and give feedback on student assignments and homework, generate lesson plans, and provide individual one-on-one tutoring, how do teachers remain relevant? (Roose, 2023)

Yet it’s important to remember that teachers have asked this question of themselves throughout time when other ‘threats’ emerged and, over and again, research supports the fact that teachers have one of the strongest impacts on student learning outcomes and results. When the Internet was launched, rather than render teachers and researchers obsolete, it instead added another dynamic to their teaching toolkit and enriched lessons and knowledge, leading to further innovation.

In his article, Roose builds on the argument that ‘with the right approach, it [ChatGPT] can be an effective teaching tool’, as demonstrated by the following example:

Cherie Shields, a high school English teacher in Oregon, told me that she had recently assigned students in one of her classes to use ChatGPT to create outlines for their essays comparing and contrasting two 19th-century short stories that touch on themes of gender and mental health: “The Story of an Hour,” by Kate Chopin, and “The Yellow Wallpaper,” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Once the outlines were generated, her students put their laptops away and wrote their essays longhand. The process, she said, had not only deepened students’ understanding of the stories. It had also taught them about interacting with AI models, and how to coax a helpful response out of one. (Roose, 2023)

Other suggestions for how ChatGPT can be a help and not a hindrance for teachers is its ability to build individualised lesson plans for students based on their unique learning and where they sit academically, generate activities for classrooms based on subject and syllabus matter, and have a first review of student homework and assessment responses and flagging potential grammatical errors, style, guidance on transitions and more. These tasks could all help to give back time to our teachers—the most treasured of all our resources and allow our teachers to focus on higher-level activities.

Director of Drama Productions, Ben Dervish-Ali, is excited about the possibilities ChatGPT brings.

Part of my role as an educator is to acknowledge what the students are using and seeing in their lives, and devise ways that this can be brought into the classroom for new learning experiences. I can see us using ChatGPT in the future as a springboard for script ideas, character development, and dialogue, and also in improv comedy sketches and exercises. I’m not worried that it will replace us as writers—the responses so far are somewhat generic and my guess is that theatre would get very boring, very quickly, if all of our dialogue came from ChatGPT. Our creativity is part of our humanity, and this can’t be replaced authentically with a chatbot. Let us instead see what benefits this technology can bring and where we go from here.

Managed carefully, ChatGPT has the potential to be another tool our teachers can use to enrich our students’ experiences, but this will be contingent on us all agreeing on an essential principle—that it is through the process of creating, of producing, of trying in which we learn. This sounds simple, but with a heavy focus on end results and measurable ‘outcomes’, we can become too worried about a perceived ‘end result’: high marks, perfect scores, desired placements, prestigious jobs, and healthy incomes.

These outcomes of course, are important to us all – we want to achieve particular, and very personal, goals. But, if our emphasis as educators is instead on the rigour and joy of learning, ChatGPT’s power diminishes – when curiosity is sparked, the desire to learn more, to expand our knowledge, usually follows.

In addition to closely monitoring developments within the context of the educational landscape, our teachers are exploring the technology first-hand to determine the benefits and issues that ChatGPT may present for them, and their students.

These findings will be considered through the lens of our School’s Academic Integrity Policy to ensure that any decision about ChatGPT – which appears here to stay – is considered, forward-thinking and not grounded in fear or reactivity. At its core, embracing the new wave of AI should hinge on how our students now and in the future seek to develop their individual character and their uniqueness of being human, and not a mere bot.

Cain, S. (2023, January 17). ‘This song sucks’: Nick Cave responds to ChatGPT song written in style of Nick Cave. The Guardian: Australia Edition. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2023/jan/17/this-song-sucks-nick-cave-responds-to-chatgpt-song-written-in-style-of-nick-cave

Roose, K. (2023, January 12). Don’t Ban ChatGPT in Schools. Teach With It. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/12/technology/chatgpt-schools-teachers.html