Bum smackers and dirty money: It seems the more things change, the more they stay the same

Some things are so bad they are worth remembering for posterity. Queensland’s crime-infested police force under the watch of corruption kingpin Terry “Sir Terence” Lewis has left such a legacy, writes David Fagan

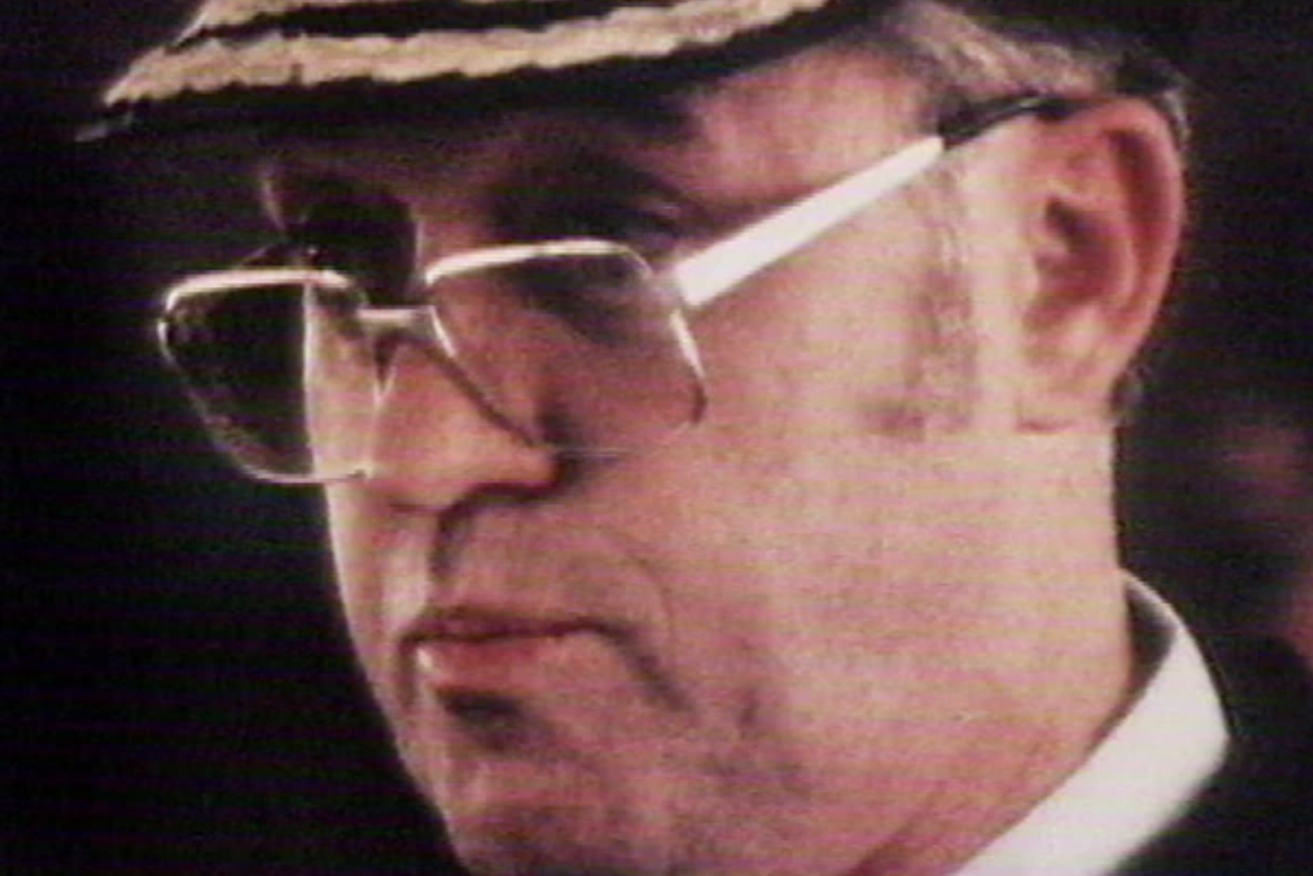

Queensland's corrupt former Police Commissioner Terry Lewis, who died on Friday (Image: ABC).

The death of the state’s corruption kingpin, Terence Murray Lewis, is yet another reminder that Queensland is no longer the place it used to be – and that’s a good thing.

Lewis insisted on his innocence until his death, claiming instead that he was the victim of an elaborate conspiracy. His denials, unbelievable as they have been, would require the public to believe he was naive and stupid in his choice of the longterm associates he accuses of “bricking” him – a practice well entrenched in the police services around Australia in the 70s. He must have thought we were stupid.

Even as a teenage student in the 70s and then a cadet journalist with a press pass signed T.M. Lewis, I knew the rumours of the corruption of Lewis and the rat pack of Tony Murphy, Glen Hallahan and Jack Herbert who were at the centre of corruption that tolerated illegal brothels and casinos in the heart of the state’s capital.

A slightly younger David Fagan is seen in his Queensland Police Pass, signed by the Commissioner of the time Terence Murray Lewis. (image, supplied).

It was the late 80s before the media did its job and pinned some facts and evidence to the rumours, prompting the Fitzgerald Inquiry. Every other institution of society, operating in fear or denial, had previously failed to clean up the system.

The media’s critics should never forget this for its work set the scene for full discovery by the Fitzgerald Inquiry that Lewis, who died at the age of 95 last week, was at the centre of a network of corruption through the 60s, 70s and 80s that penetrated the police service, politics, the electoral system and every level of public administration, including the Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

So where has this got us? We now have accountability mechanisms that mean we can go about life confident that the police (notwithstanding their continued cultural shortcomings) are not running vice or gambling. Their ability to do so has been diminished by the legalisation and licensing of what were once crimes.

This has presented other problems. While casino gambling is now legal, the use of Queensland’s casinos to launder hundreds of millions of illegally gained cash went undetected by either police or the gambling regulators – and, so far, no one has been prosecuted let alone convicted of industrial scale money laundering.

And we can be confident (notwithstanding their many shortcomings) that politicians are not choosing to turn a blind eye to crime even if they have reduced interest in accountability as evidenced by slow implementation of the Coaldrake review last year.

And now, the concerns about crime have turned to the inability of the law and police to contain a youth crime outbreak, justifiably highlighted in the media. This is not corruption but poses a more visible threat to more people than the corruption of the 80s. There is an inevitable political price to pay for this, particularly as the appetite for community-led responses grows.

Ironically, the risk from young people turning to crime was at the centre of Terence Murray Lewis’s rise from largely unknown membership of a corrupt police ring to the top of the police service. Through much of the 60s and 70s (before being picked from obscurity to become Deputy then Police Commissioner), Lewis ran the Juvenile Aid Bureau.

Its focus was to zero in on youth offenders – vandals, shoplifters, truants and street fighters – before their crime reached a serious level. In those days, Lewis (while still collecting corrupt payments through his crooked network) advocated a reforming approach guided by the current psychology and practices he had learnt while at university night classes.

The bureau was known as the “bum smackers”, reference to what other police saw as its soft approach.

It’s hard to reconcile the two approaches – a man corrupt to the eyeballs on one hand but seemingly compassionate in getting kids on the straight and narrow on the other.

The current youth crime outbreak is marked by crimes far worse than those Lewis was dealing with in the straight hours of his job. Bum smacking is no longer a reasonable response but nor does anything else look like working.

We have achieved so much since the 80s in creating a mature political and legal system but its true measure is its capability to serve the community with responses, not just denials that ultimately are futile.